Common name

Channel-Billed Toucan or Common Toucan

Scientific name

Ramphastos vitellinus

Genus

Ramphastos

Etymology

New Latin, irregular from Greek “rhamphos” translates to “curved beak” and “astos” translates to “citizen”, from “asty”, meaning “city”. The earliest known usage of the word “toucan” in English dates from the 16th century, refering to a bright-colored bird of South America, 1560s, from French toucan (1550s) and Spanish tucan; from Tupi (Brazil) tuka, tukana, said to be probably imitative of its call.

Taxonomy

The subspecies was previously considered to be a separate species, but all interbreed freely wherever they meet. These are the yellow-ridged toucan (Ramphastos culminatus; now Ramphastos vitellinus culminatus), the citron-throated toucan (Ramphastos citreolaemus; now Ramphastos vitellinus citreolaemus) and the Ariel toucan (Ramphastos ariel; now Ramphastos vitellinus ariel). However, the subspecies Ramphastos vitellinus ariel is closer to Ramphastos vitellinus culminatus than to the nominate, and are by some already considered close to distinct species status. As Ramphastos vitellinus ariel was described before Ramphastos vitellinus culminatus, if separated they would become Ramphastos ariel ariel and Ramphastos ariel culminatus. There also exists an isolated population in eastern Brazil. It looks very similar to, and has traditionally been considered part of, Ramphastos vitellinus ariel, but molecular analysis suggests that it has been isolated for a long time and is a yet undescribed, separate subspecies, or possibly even species (Weckstein, 2005).

Fly tying

The historically correct material, is the golden breast feather from the Ariel Toucan.

Substitute suggestions

– Swan or Goose neck feathers dyed golden yellow (by far the most realistic sub).

– Flat Golden pheasant crest (found between crests and tippets).

– Dyed Magpie.

– Yellow Weaver.

– Yellow Breasted Pigeon.

– Yellow Oriole.

Many also up CDC (Cul de Canard) dyed yellow as a sub. While the feathers are of the same size, and of the same shape, CDC is essentially too stiff to successfully make it look like Toucan. Even for fishing flies, it is too far from the real thing, in my honest opinion.

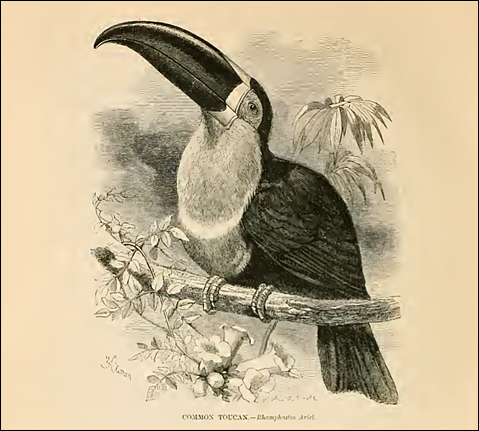

A description from the 19th century

The following text is quoted from Illustrated Natural History 2: Birds, by J.G. Wood, published in 1859.

The very curious birds that go by the name of Toucans are not one whit less remarkable than the hornbills, their beak being often as extravagantly large, and their colours by far superior. They are inhabitants of America, the greater number of species being found in the tropical regions of that country.

The very curious birds that go by the name of Toucans are not one whit less remarkable than the hornbills, their beak being often as extravagantly large, and their colours by far superior. They are inhabitants of America, the greater number of species being found in the tropical regions of that country.

Of these birds there are many species, of which no less than five were living in the Zoological Gardens in a single year. Mr.Gould, in his magnificent work, the “Monograph of the Rhamphastidae”, figures fifty-one species, and ranks them under six genera.

Unlike the hornbills, whose plumage is of a sober cast, the Toucans are gorgeously clothed in every colour of the rainbow ; and from the peculiar texture of the feathers, these brilliant tints possess a purity which is seldom seen elsewhere. There is hardly a shade of colour which may not be found in these birds, whose plumage would give admirable hints to the student of colouring. In some species, and often in the same individual, the intensest carmine, azure, emerald-green, orange, and gold, may be seen suddenly contrasted with jetty black and snowy white, while in others the feathers are tinged with the softest and most delicate grey, lilac, pink, and primrose. Unfortunately, many of these colours are so intimately connected with the life of the bird, that they fade immediately after its death, and cannot be restored by any known art of man.

In one species, the Curl-crested Aracari, the feathers of the head assume a most unique and somewhat grotesque form, reminding the observer of a coachman’s wig dyed black. On the top of the head the shafts of the feathers, instead of spreading out into webs, become flattened, and are rolled into a profusion of bright shining curls, so that the bird really appears to have been under the tongs of the hairdresser. Indeed, it appears almost impossible that this singular arrangement of the feathers should not be the work of art.

The most extraordinary part of these birds is the enormous beak, which in some species, such as the Toco Toucan, is of gigantic dimensions, seeming big enough to give its owner a perpetual headache, while in others, such as the Toucanets, it is not so large as to attract much attention.

As in the case of the hornbills, their beak is very thin and is strengthened by a vast number of honeycomb-cells, so that it is very light and does not incommode the bird in the least. In performing the usual duties of a beak, such as picking up food and pluming the feathers, this apparently unwieldy beak is used with perfect address, and even in flight its weight does not incommode its owner.

The beak partakes of the brilliant colouring which decorates the plumage, but its beautiful hues are sadly evanescent, often disappearing or changing so thoroughly as to give no intimation of their former beauty. The prevailing colour seems to be yellow, and the next in order is red, but there is hardly a hue that is not found on the beak of one or other of the species. As examples of the colouring of the beaks, we will mention the following species. In the Toco Toucan it is bright ruddy orange, with a large black oval spot near the extremity ; in the Short-billed Toucan it is light green, edged and tipped with red ; in the Tocard Toucan it is orange above and chocolate below ; in the Red-billed Toucan it is light scarlet and yellow ; in Cuvier’s Toucan it is bright yellow and black, with a lilac base ; in the Curl-crested Aracari it is orange, blue, chocolate, and white ; in the Yellow-billed Toucan it is wholly of a creamy yellow, while in Azara’s Aracari it is cream-white with a broad blood-red stripe along the middle. Perhaps the most remarkable bill of all the species is found in the Laminated Hill Toucan (Andigena laminatus), where the bill is black, with a blood-red base, and has a large buff-coloured shield of horny substance at each side of the upper mandible, the end next the base being fused into the beak, and the other end free. The use of this singular, and I believe unique, appendage is not known.

The flight of the Toucan is quick, and the mode of carrying the head seems to vary in different species, some holding their heads rather high, while others suffer them to droop. Writers on this subject, and indeed on every point in the history of these birds, are rather contradictory ; and we may assume that each bird may vary its mode of flight or carriage in order to suit its convenience at the time. On the ground they get along with a rather awkward hopping movement, their legs being kept widely apart. In ascending a tree the Toucan does not climb, but ascends by a series of jumps from one branch to another, and has a great predilection for the very tops of the loftiest trees, where no missile except a rifle ball can reach him.

The voice of the Toucan is hoarse and rather disagreeable, and is in many cases rather articulate. In one species the cry resembles the word “Tucano”, which has given origin to the peculiar name by which the whole group is designated. They have a habit of sitting on the branches in flocks, having a sentinel to guard them, and are fond of lifting up their beaks, clattering them together, and shouting hoarsely, from which custom the natives term them Preacher-birds. Sometimes the whole party, including the sentinel, set up a simultaneous yell, which is so deafeningly loud that it can be heard at the distance of a mile. They are very loquacious birds, and are often discovered through their perpetual chattering.

Grotesque as is their appearance, they have a great hatred of birds who they think to be uglier than themselves, and will surround and “mob” an unfortunate owl that by chance has got into the daylight with as much zest as is displayed by our crows and magpies at home under similar circumstances. While engaged in this amusement, they get round the poor bird in a circle, and shout at him so, that wherever he turns he sees nothing but great snapping bills, a number of tails bobbing regularly up and down, and threatening gestures in every direction.

In their wild state their food seems to be mostly of a vegetable nature, except in the breeding season, when they repair to the nests of the white ant which have been softened by the rain, break down the walls with their strong beaks, and devour the insects wholesale. One writer says that during the breeding season they live exclusively on this diet. They are very fond of oranges and guavas, and often make such havoc among the fruit-trees, that they are shot by the owner, who revenges himself by eating them, as their flesh is very delicate. In the cool time of the year they are killed in great numbers merely for the purposes of the table.

In domestication they feed on almost any substance, whether animal or vegetable, and are very fond of mice and young birds, which they kill by a sharp grip of the tremendous beak, and pull it to pieces as daintily as a jackdaw or magpie. One Toucan, belonging to a friend, killed himself by eating too many ball-cartridges on board a man-of-war. As the habits of most of these birds are very similar, only one species has been figured, for the description of other species would necessarily have been limited to a mere detail of colouring.

When settling itself to sleep, the Toucan packs itself up in a very systematic manner, supporting its huge beak by resting it on its back, and tucking it completely among the feathers, while it doubles its tail across its back, just as if it moved on a spring hinge. So completely is the bill hidden among the feathers, that hardly a trace of it is visible in spite of its great size and bright colour, and the bird when sleeping looks like a great ball of loose feathers.

Another description from the 19th century

The following text is quoted from the Royal Natural History volume 3, section 6 (R. Lydekker 1895)

Gaudy in plumage, and ungainly in appearance, these large-billed birds arc denizens of the tropical forests of Central and South America, also extruding to those of Northern Mexico, almost within sight of the Rio Grande. Resembling the woodpeckers and barbets in the internal structure of their zygodactyly feet, they differ in having the front end of the vomer truncated in the Passerine manner.

For the size of its owner the bill among the toucans is of enormous dimensions, giving to these birds an almost ludicrous look. If solid, the appendage would be far too heavy to carry : but in reality it is extremely light. Being very thin, and the interior occupied by a fine network of bony fibres, arranged so as to give great strength to the external parietes without weight. The tongue of these birds is likewise peculiar, the anterior portion consisting of a bony, narrow, thin plate, flattened horizontally, and supported bya process of the tongue-bone, which forms a ridge beneath it. Measuring nearly 6 inches in length in the larger species, at about 4 inches from its extremity it is obliquely notched on both sides ; these notches becoming deeper and deeper towards the apex, thus giving it a bristly appearance. Resembling the barbets in having a tufted oil-gland, the toucans also agree with these birds in the presence of ten feathers to the tail. The beak is generally highly coloured ; while frequently the bare face partakes of the same brilliant hues.

When asleep, toucans have a curious way of carrying the tail, which is turned up over the back, while the enormous beak is buried beneath the scapular feathers. According to Dr. Sclater’s arrangement, toucans may be divided into five genera ; namely, Rhamphastus with fourteen, Andigena with six, Pteroglossus with eighteen, Selenidera with seven, and Aulacorhamphus with fourteen species; the number of toucans now known thus being fiftynine.

According to the account of Prince Maxmilian, “these birds are very common in all parts of the extensive forests of the Brazils, and are killed in great numbers at the cooler portion of the year, for the purposes of the table. To the stranger they are of even greater interest than to the natives, from their remarkable form, and from the rich and strongly contrasted style of their colouring, their black and green bodies being adorned with markings of the most brilliant hues—red, orange, blue, and white; the naked parts of the body being dyed with brilliant colours ; the legs blue or green the irides blue, yellow, etc. ; and the large bill of a different colour in every species, and in many instances very gaily marked. In their habits the toucans offer some resemblance to the crows, and especially to the magpies ; like them they are very troublesome to the birds of prey, particularly to the owls, whom they surround and annoy by making a great noise, all the while jerking their tails upwards and downwards. The flight of these birds is easy and graceful, and they sweep with facility over the loftiest trees of their native forests, their strongly developed bills, contrary to expectation, being no encumbrance to them. The voice of the toucans is short and unmelodious, and somewhat differed in every species”.

Aracari Toucans.

Of the smaller-billed toucans, some of the best known are the so-called aracaris {Pteroglossus) ; and an incident recorded by Mr. Stolzmann, during his travels in Peru, shows how difficult these birds are to see in their forest surroundings, his experience being very similar to that of Bates with the curl-crestedtoucan (P.beauharnasi) on the Amazon. Stolzmann says that when procuring a pair of the yellow-billed aracari (P. fiavirostris), or yurimaguas, he fired in a high tree at a bird, which uttered some piercing cries as it fell, and in a moment he was surrounded by ten of the birds, keeping up a fearful din. On a second shot being fired, they all disappeared. This circumstance proves, as he says,that although only one individual can be seen, it does not follow that there are no more in the neighbourhood, as they are, in fact, always in little troops, according to the general habit of toucans in Peru.

Of the smaller-billed toucans, some of the best known are the so-called aracaris {Pteroglossus) ; and an incident recorded by Mr. Stolzmann, during his travels in Peru, shows how difficult these birds are to see in their forest surroundings, his experience being very similar to that of Bates with the curl-crestedtoucan (P.beauharnasi) on the Amazon. Stolzmann says that when procuring a pair of the yellow-billed aracari (P. fiavirostris), or yurimaguas, he fired in a high tree at a bird, which uttered some piercing cries as it fell, and in a moment he was surrounded by ten of the birds, keeping up a fearful din. On a second shot being fired, they all disappeared. This circumstance proves, as he says,that although only one individual can be seen, it does not follow that there are no more in the neighbourhood, as they are, in fact, always in little troops, according to the general habit of toucans in Peru.